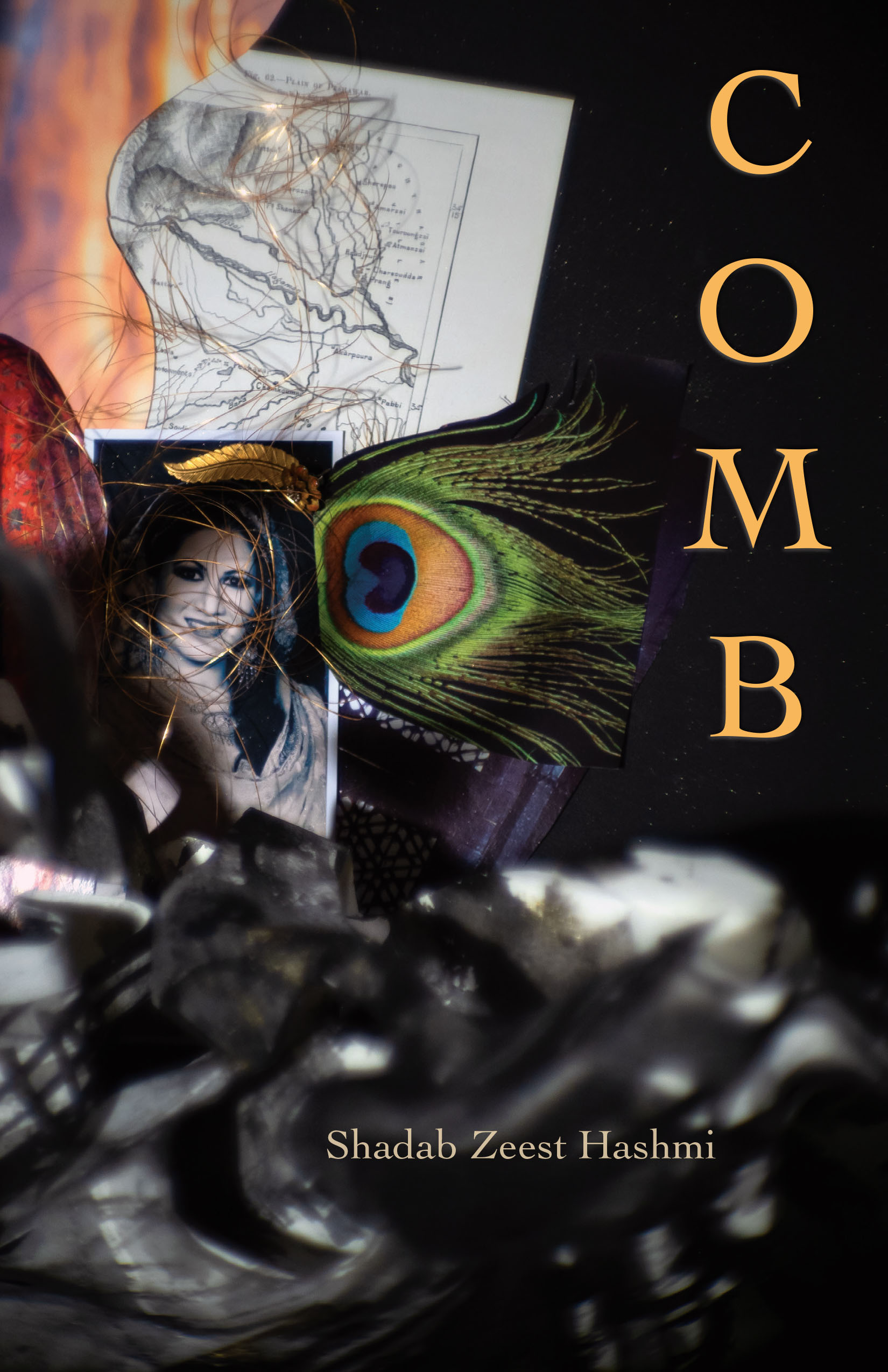

Comb is the story of a girl “under the spell of history,” growing up in the shadow of the legendary Khyber Pass which is both a bridge between disparate civilizations and an impassable divide. Shadab Zeest Hashmi reveals the tangles of empire and language, history and myth, exile and belonging — from the lens of childhood, integrating memory with the history of one of the most significant geopolitical and cultural thresholds of the world. This is a book that honors thresholds in a time of closed doors, written with a poet’s conviction in the regency of love.

The Language of Loss

The Language of Loss contains tanka and haiku of exceptional quality. But it is the remarkable way in which the poet links tanka and haiku that elevated The Language of Loss into the winner’s circle. The poems on each page come together in a conversation of many layers. That these conversations will deepen and change for each reader is due to the author’s expertise. I am delighted to congratulate Debbie Strange on her winning collection.

Room Meant for Music

The List of Last Tries, by Jessica Walsh

Jessica Walsh’s The List of Last Tries is a miracle of focus, a sustained gothic nursery rhyme that describes a girl’s coming of age and coming into power, for which she is shunned and exiled as freak, witch, and murderer. She “split(s) worms lengthwise,” “pop(s) open cow eyes,” and even eats a bug in defiance of the conventional shrieks of other girls.

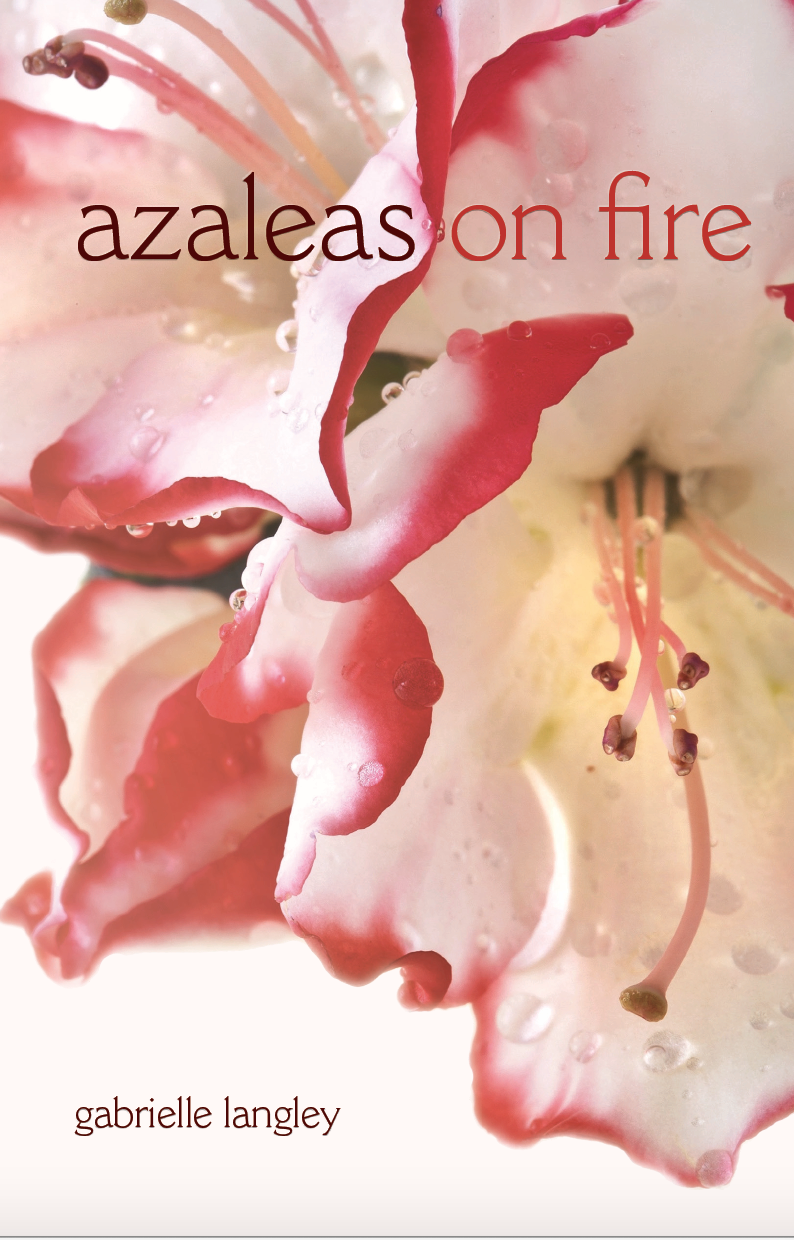

Azaleas on Fire, by Gabrielle Langley

Conceived “in the month of pearls” as she tells us in her poem “Birthstone,” Gabrielle Langley is a poet of true luminosity, stringing her “English words like pearls” across continents — from Paris and Milan to Katyn and Istanbul, Lebanon and beyond. I find her to be a remarkable imagist of postmodernity. In Azaleas on Fire, she leads her reader through gardens of flowers rescued from romantic tradition through irony where the fragrance of narcissus and gardenias meets charred wood, “the burn of salt water rising to swallow small children.” She weaves delicacy with strength, a floral lace that is beautiful, tough, untearable.

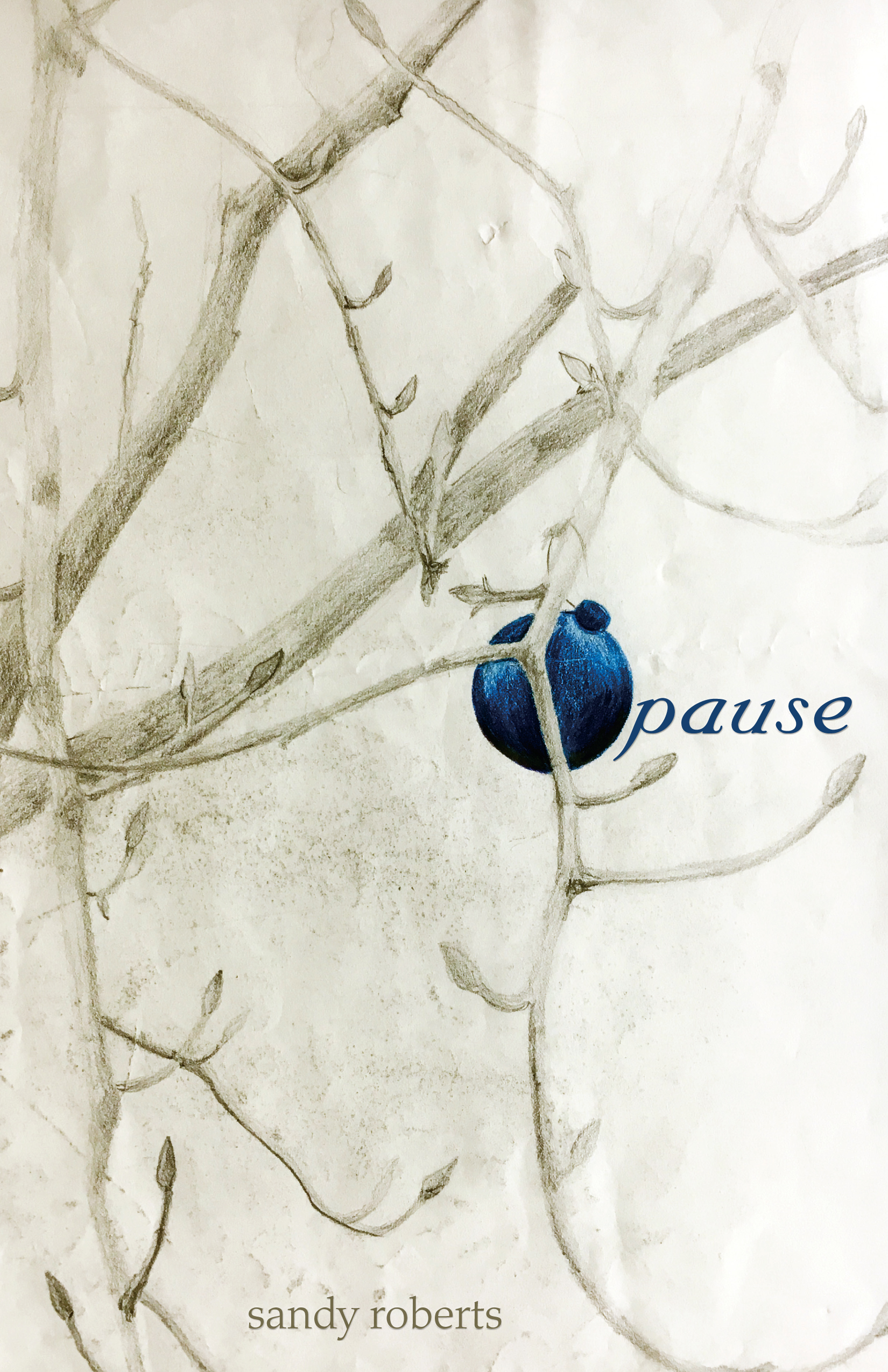

Pause, by Sandy Roberts

With gentle imagery and language, Sandy Roberts explores her own spiritual roots and survival of growing up in the deep South of 1940’s Texas, and the pain and hardship of the changing physical and political landscape.

Emily Dickinson kept at her side the two same books that were prominent in Sandy’s own childhood home – the dictionary and the bible. Perhaps those books were enough to plant the seed to love words, language, and the images and the connections.

Eating the Light, by Mary Barbara Moore

In Eating the Light, these new poems of Mary Moore ‘s new poems offer a feast for the reader. On subjects both natural and human-wrought, her eye is the painter’s: vividly clear. She creates an appetite for looking and a fulfillment of seeing. Moore’s perceptions are sensuous, intelligent, and the world in the poems is a world transformed both physically and emotionally. Her metaphors illuminate and satisfy, and having dined with her, we begin to glow, sated on such delectables. These poems embody a kind of mystical sensitivity to the sources of life: immediate, continuously perishing, making its considerable mark in these gorgeous lines.

Return, by Cristina Albers

This collection is a powerful testament to the ebb and flow/ highs and lows of early recovery. Return provides a glimpse into a process seldom seen. The process of recovery skillfully woven into a poetic style of descriptive precision. Return is a snapshot of body bags, key tags, 90 day intervals and the triumph of that first year of freedom. For this poet, this is only the beginning.

Sacajawea’s Song, by Judith Fuller

The history of Sacajawea, who traveled with Lewis & Clark on their expedition, has been documented by the writings in their journals, and her story has been told and retold through the years, even to our school children. But how often do we get a chance to travel along with Sacajawea on her inner journey as well?

Sacajawea’s Song is the beautifully-imagined journey — both across the land and the landscape of the heart — of one of this country’s best-known native daughters, Sacajawea.

Breasts Don’t Lie, by Trudi Young Taylor, Ph.D.

Trudi Taylor’s challenging and thoughtful book about breasts will surprise you with its wit and insight. It shakes off the stereotypes men have about women’s breasts, and more importantly, forces women to really think about and honor their bodies and their breasts, whether they are firm, floppy, big, tiny buds, or surgically scarred. Read it for yourself. Share it with someone you love. Spend an evening with friends talking about the stories and working through the exercises. But, most important of all, have your son or daughter read this book and talk to them about loving others and loving themselves.